Clark’s Crystal Ball

Clark sharpens its focus to assist students in succeeding in a fast-changing world

6-minute read

In its 90th year, Clark College is looking to the future. Like other colleges and universities, Clark faces unprecedented challenges including an economy that discourages college enrollment, shifting student demographics and the aftershocks of the COVID-19 pandemic. But each challenge brings with it an opportunity.

In gearing up for the future, Clark has sharpened its focus on equity. When Clark’s president, Dr. Karin Edwards, took the helm in 2020, she committed to closing disparities and using an “equity lens” to review college policies from hiring practices to curricula to student services.

Today, 35% to 40% of Clark students belong to groups that are non- dominant. In other words, Clark’s student body is diversifying.

Clark is an engine of transformation. When one person earns a college degree and begins their career, it elevates the whole family’s income and opens doors for the next generation. That means making Clark a more equitable college—and helping historically underserved communities—will make Southwest Washington a more equitable community.

Clark College’s Board of Trustees and executive cabinet members are finalizing an equity centered strategic plan to guide the institution through 2027. Here are four individuals whose stories and experiences connect to the four tenets of that plan.

Equitable student experience | Sarah Jones, welding

Clark’s Sarah Jones is one of several female welding students studying to enter a traditionally male-dominated industry.

Sarah Jones, 18, is one of a handful of female welding students at Clark who are studying to enter a traditionally male-dominated industry. When she completes her certificate of proficiency in June, Jones will apply for an apprenticeship with the local pipe fitters’ union.

Jones did her research and discovered that, within the welding industry, pipefitting is “where the money’s at.” According to Washington’s Office of Financial Management, union pipefitters hired by the state in 2022 earned an annual salary of $57,324 to $71,520.

Jones was diagnosed with dyslexia in third grade and knew by the end of high school that she was best suited for the trades.

“Working with my hands is just something I excel at, rather than learning from a book,” she said. She researched the construction trades and liked the idea of welding because she has “a really good attention for detail.”

Booming economy

Welders are in demand now and Jones expects to find a manufacturing job upon completion of her certificate and while she waits for an apprenticeship. She said she looks forward to changing people’s perceptions of what a welder looks like.

Despite the unmet demand, Clark has vacancies in its welding program. Community colleges generally see enrollment rise during a recession and drop when the economy is booming. The current economy is an unusual mix of the two.

“For younger people, it’s a pretty booming economy right now,” said Paul Speer, chair of Clark College’s Board of Trustees. “Someone right out of high school can make $25 an hour as a barista.”

Clark is preparing for a slightly older student body in the coming years, as high school graduates eschew college and enter the workforce before realizing that they need more training to earn more in the future. Older student cohorts have different needs and interests than younger ones. More students could be balancing college while raising families, for example.

Clark is also reckoning with a future that could include fewer students overall. From the 1970s until 2007, the birth rate in the United States was relatively stable. Then it started dropping, which was an aftereffect of the Great Recession. As babies born during that era turn college age, experts in higher education brace for what they call “the enrollment cliff.” This puts even more pressure on college leadership to spend limited resources wisely.

Speer said Clark has reinvented itself many times in its 90-year history. The college once suspended operations when enrollment plummeted during World War II. When the war ended, students re-enrolled and courses resumed.

“Clark,” Speer said, “will always be this community’s college.”

Employee engagement | Professor Alejandra Maciulewicz-Herring

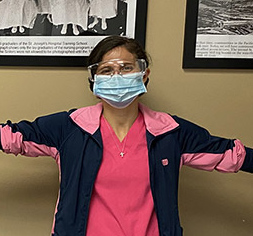

Alejandra Maciulewicz-Herring ’13 started her first teaching job at Clark’s medical assisting program in 2020. It was a seismic shift for her to go from a clinical setting to the novelty of working remotely.

Maciulewicz-Herring suspected that some of her co-workers had been her teachers when she attended Clark’s certified nursing assistant program years earlier. But the two programs have different faculty and without bumping into people in the halls and seeing them in person, Maciulewicz-Herring couldn’t be sure.

Alejandra Maciulewicz-Herring ’13 started her first teaching job at Clark’s medical assisting program. Today she’s a tenured professor.

The pandemic exacerbated disparities in Southwest Washington and beyond. While some students thrived as education switched online, others faltered. Educators themselves experienced varied responses to the new modes of teaching and learning. More recently, the return to in-person learning was rough for some faculty and staff.

Some longer-term faculty are experiencing burnout. Clark, like other community colleges, has struggled to hire and retain faculty. Health care, trades and cybersecurity are a few industries where people with skills and experience easily earn more than community college instructors, whose salaries are set by the state.

Under the new strategic plan, Clark will measure its progress toward specific goals, such as fostering “employee engagement through open communication, transparency and involvement in key decisions.”

For Maciulewicz-Herring, it has been rewarding to train people to work in the community.

“There is huge demand for [medical assistants] right now,” she said. Partner organizations hire graduates right away. Wages are up and new jobs such as a traveling medical assistant are available.

Volunteering is key

Medical assistants have clinical and administrative responsibilities. They administer injections, take blood pressure readings and draw blood as well as keep care providers on schedule and call insurance companies with billing questions. Medical assisting can also be a steppingstone to other careers such as nursing or hospital administration.

In early 2021, Maciulewicz-Herring and other Clark faculty volunteered at PeaceHealth Southwest Medical Center to vaccinate patients against COVID-19. A former vaccine coordinator, she saw the mass vaccination event as a massive logistical feat.

“It was really exciting to see Clark supporting the local community,” she added. She worked alongside her colleagues in person and was filled with hope that the new vaccine was the beginning of the end of the pandemic.

Maciulewicz-Herring said her students are entering the profession because they want to make a positive difference.

“I tell them, in order to make a huge impact, you have to make the time to volunteer in your community,” she said. These opportunities provide real-life work experiences that benefit students, promote Clark’s allied health programs and strengthen the health of the community.

Planning ahead

Although the new strategic plan guides only the college, Clark College Foundation CEO Calen Ouellette said it also provides the foundation with an opportunity to better achieve its own mission.

“As the college sharpens its own goals and priorities, we can become a more effective partner institution,” Ouellette said. “A clear plan for Clark’s future helps us determine how we can best support the college and its students.”

Community engagement | Adrienne Watson, PeaceHealth

Adrienne Watson had a medical procedure when she was 14 and remembers coming out of anesthesia in a recovery room. A nurse in the room didn’t say much, Watson said, but “I thought, ‘okay, I am safe.’ There is an art to nursing … and that was someone who had mastered the art.”

Years later, as she considered her career choices, Watson recalled that nurse and thought, “I want to make people feel safe.”

Watson worked as a clinical nurse for 18 years before switching to administration for the next 18 years. Today, she is system director of clinical education at PeaceHealth.

Adrienne Watson is responsible for PeaceHealth’s clinical affiliation agreements with institutions like Clark. PeaceHealth is the single largest employer of Clark College graduates.

In the classroom, nursing students learn job skills. But it takes a clinical rotation, Watson said, to learn how their skills and knowledge apply in the real world.

Clark is a pipeline

Being a nurse is “like being a conductor of all of these different roles involved in a patient’s care,” Watson said. “You don’t see that in a classroom; you experience it in a clinical rotation.”

Watson is responsible for PeaceHealth’s clinical affiliation agreements with institutions like Clark. PeaceHealth is the single largest employer of Clark College graduates.

“Clark is really a pipeline to bring nurses into [PeaceHealth]. We try to stay well connected,” Watson said.

As a member of Clark’s nursing program advisory board, Watson reviews curricula and asks questions to ensure faculty are teaching the most up-to-date practices. She sees room for Clark and PeaceHealth to work together even more closely.

“I would like to find more ways for direct care nurses to become adjunct faculty or clinical faculty, so they have a way to impart their knowledge on students earlier,” she said.

More nurses would teach if it didn’t require quitting their clinical jobs and taking pay cuts, Watson said.

Hospitals that host simulation events for nursing students offer another potential area for growth. Watson wants clinicians to be part of the grading, coaching and training for these assignments, to make them more realistic.

Speer, the trustee, said the college sees opportunities for other departments to partner with private businesses, too. These relationships are essential, he said, to ensure that Clark is teaching the skills the community needs.

Institutional effectiveness and equity | Alex Herrboldt ’16, PAX Learning Center

When Alex Herrboldt ’16 graduated from high school, he didn’t know what he wanted to do. He enrolled at Clark to explore his interests. Rather than rush his education, he enrolled as a part-time student and took his time. He earned his associate degree in four years rather than the usual two.

To pay for his education, he got a work- study job tutoring adult GED students in Clark’s transitional studies tutoring department. Herrboldt worked there all four years while he was at Clark, eventually serving as a program coordinator. It was that experience—not the academic courses—that led to Herrboldt’s passion and career.

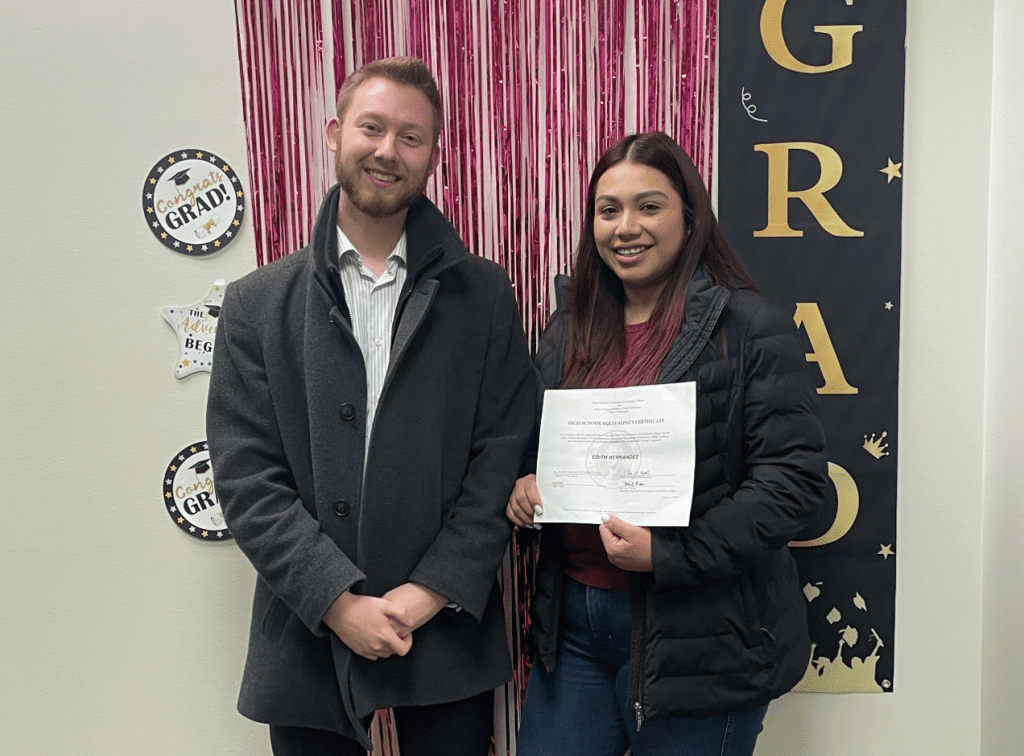

Today, Herrboldt is co-founder and executive director of the PAX Learning Center, a nonprofit tutoring resource that helps people earn their GED certificates or high school diploma equivalents. Clark still offers GED testing and preparation classes but some of the community support services it used to offer are now provided by organizations such as PAX.

Self-paced

Standard GED curricula prescribe specific materials at a specific pace. The foundational belief of PAX is that students should learn at their own pace.

“It allows them to take hold of their own education. If they run into something they know well and they can demonstrate it, they don’t have to spend a week on it,” he said. “If they need extra practice, they take their time and aren’t made to feel like they’re slow.”

Alex Herrboldt ’16 is co-founder and executive director of the PAX Learning Center, a nonprofit tutoring resource helping people earn GED certificates or high school diploma equivalents.

PAX provides a supportive and encouraging learning environment, a low ratio of volunteer tutors to students and varied locations and hours, including online options.

As Clark reviews its own equitable and sustainable use of resources, it may rely more on community organizations like PAX to prepare students for college. Then, when they are ready for Clark, the college will be ready for them.

While four-year universities offer increasingly expensive—and often debt-laden—degrees, Clark is well positioned as an affordable alternative.

PAX has helped hundreds of people in Southwest Washington earn their GED certificates since opening in 2019. Herrboldt said that many have gone on to attend Clark.

“A GED is life-changing,” Herrboldt said. And watching the students gain self-confidence

as they inch closer to new pathways has been equally rewarding for Herrboldt.

Written by Lily Raff McCaulou