Clark alumnus Denis Hayes on creating super green cities

By Rhonda Morin

When Clark alumnus Denis Hayes was in his early 20s, he went on a quest to find his calling, hitching around the world for three years. His adventures took him throughout Africa, from its west to east coast; throughout the Middle East, then south-southwest; and finally to Southeast Asia.

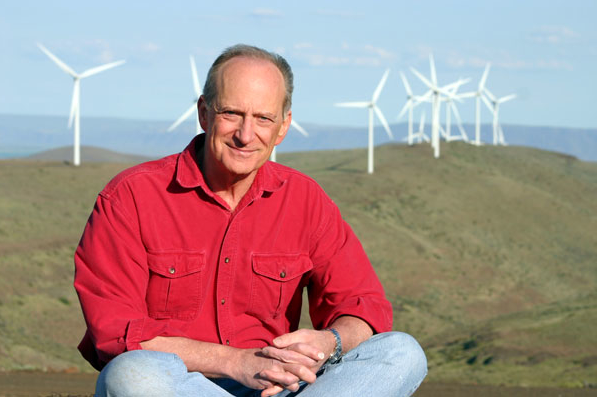

“It was a profoundly important period for me. It was an awakening for me,” said Hayes, a 1964 Clark graduate and CEO of the conservation group Bullitt Foundation in Seattle, during a virtual event on February 23, 2021, presented by Clark College Foundation’s Alumni Relations office.

While on that journey, he had ample time to think about his future and the effects humans were having on the planet. At one pivotal moment, he came to understand that humans live inside ecosystems just like all other animals, but with a central difference: people had tapped into cheap, abundant energy that allowed us to take advantage of and abuse the Earth. Because of how we were using energy and extracting it, the world in the 1960s was teeming with environmental problems.

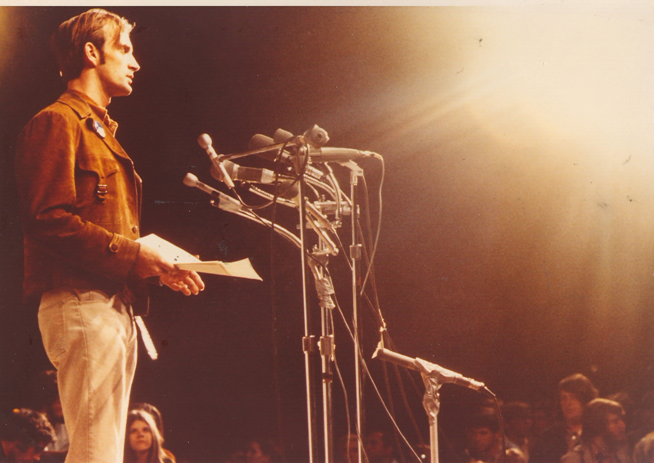

Denis Hayes speaking at the ellipse on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. in 1970. Photo courtesy of Denis Hayes

Hayes, now 76, grew up in Camas, Wash., where pollution from the town’s paper mill permeated his childhood.

“Camas is in one of the most spectacularly beautiful and biologically diverse parts of the planet. But the mill filled the air with unregulated poisons; it poured enormous volumes of toxic effluent into the river; it mowed down the surrounding Douglas fir forests in devastating clear cuts, losing rich topsoil and decimating fragile ecosystems,” Hayes told the Camas-Washougal Post-Record newspaper in 2015.

Those formative years left an indelible mark on the future environmentalist. Later, when he enrolled at Clark College in Vancouver, he recalls how his instructors helped him ignite his inquisitiveness and harness his enthusiasm into critical thinking.

“Some of the teachers that I had at Clark were as superb as any teachers I had encountered anywhere. They took a real interest in their students [and] took a real interest in me. I started to ask a whole lot of probing questions about the assumptions I had taken on faith before then. It was the first part of my intellectual awakening.”

Stanford Law School and Harvard Kennedy School followed. But, it was the hitching trip across Africa and the Middle East that proved to be his clearest compass bearing.

Super green cities

The year 1970 was significant for Hayes. On April 22 of that year, the first Earth Day was held bringing an estimated 20 million people together and launching a cohesive environmental movement from what had been disjointed groups of random activism. Hayes was the lead organizer behind the Earth-friendly event. What started as a teach-in that he was organizing for Sen. Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin, turned into a global affair.

“What we did on that first Earth Day was to take all those individual strands and weave them into modern environmentalism,” he said.

What followed that epic event changed the way the world thought about and interacted with the planet.

Hayes discussed this topic and many more during the virtual question-and-answer event in February called Creating Super Green Cities. Recent graduate Kenia Torres-Rosas ’20 and current student Justin Hymas asked Hayes questions submitted by guests before the event.

Hayes talked about the intersections between creating super green cities and being homeless, overpopulation, job growth, alternative energy sources and socially conscious corporations. He also suggested ways Clark students can make a difference in the climate.

In the years following that first ambitious Earth Day, a rapid succession of legislation unanimously voted in at the federal level—clean air, safe drinking water, endangered species acts, marine mammal conservation act, toxic substances control act—put in place the framework around new corporate behavior.

There was a long dry spell following those laws, but in recent years, there has been an uptick in corporate responsibility around the environment, with a particular focus on sustainability. Companies want to endure for the next 30 to 50 years; to do that, they must improve their behavior to survive.

“Microsoft pledged it’ll be net-carbon neutral by 2030, and by 2050 it will be sufficiently carbon negative—that means it will have taken out of the atmosphere as much carbon as it has put into the atmosphere during its entire corporate existence,” said Hayes, citing one example.

Another is General Motors, which dramatically reversed course from a 2020 lawsuit that supported undercutting clean air and greenhouse gas obligations put in place by California. Now GM has committed to producing no cars that use internal combustion or diesel engines after 2035.

“We’re talking about serious, fundamental corporate commitments coming from a few places,” he said.

Energy revolution

One question from the audience asked about the effects of stable social living given the gulf between the rich and poor. Hayes predicts the energy revolution will make fewer people and entities wealthy. Each of humanity’s revolutions—agriculture, industrial, digital—has triggered a great concentration of wealth for a few in its wake. He doesn’t see the same thing happening in what he calls the energy revolution: how humans fundamentally change how we get our energy and how we use it once it’s extracted.

Denis Hayes is a Clark College alumnus and head of the Bullitt Foundation, a conservation group in Seattle. Photo courtesy of Denis Hayes

Sources like solar, geo-thermal or wind, which are modular and distributable, can be built small scale and distributed across society, making it unlikely that only a handful of savvy entrepreneurs would benefit from the windfall.

The endgame to the energy revolution, says Hayes, is to stop making materials from petroleum.

“Ultimately, what we’re trying to do is design a system that is not going to produce combustible plastics out of oil.”

Furthermore, our energy production cycle would become circular: produce energy, reuse it, recycle it and re-engineer it to keep it going. The aspiration is to keep products in circulation, rather than combusting them, he added.

The world is an energy fiend; it gobbles up coal, oil, gas, wind, solar, geothermal and other sources to power the services and support we humans use each day. Hayes believes changes in behavior can drive down energy demands, making renewable sources like solar and wind more plentiful to meet the world’s energy needs.

“By 2050, the world will be getting 90-percent-plus of its energy from renewable resources, from predominantly solar and wind, although we’ll continue to produce a little bit more hydro than we are today. We’ll be seeing more and more geothermal, particularly deep geothermal, come online,” he says.

What is overlooked, he added, is that humans need to embrace and invest in efficiency.

“The whole concept of waste as a source of status has to somehow be abandoned. The fact of getting from one point to another by driving a 2-ton sports utility vehicle to transport a 160-pound person is just literally crazy. Much of the world is getting away from that.”

Student ambitions

There are many more fields of study pertaining to the environment these days than when Hayes was in college. His advice for Clark students interested in climate science is to look at studying ecological economics, environmental history or environmental law.

Other advice he offers to students extends to us all: make responsible choices that reduce waste in our everyday lives. This includes changing modes of transportation, bringing food from home while at work or school, eating organic if it is affordable, encouraging food services to compost or donate their excess food to those in need.

“The whole thing comes down to integrity. Live the values you proclaim so you’re more motivated yourself to give it your all and you’re not a hypocrite.”

Rhonda Morin is the editor in chief of Clark Partners magazine.