The Language of Medicine

Human cadavers offer a unique learning experience unparalleled by books or plastic models

By Rhonda Morin

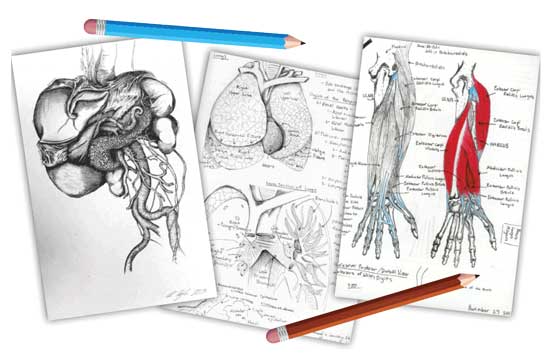

When second-year Nursing student Dustin Carlson hears a patient talk about radiating leg pain, a clear picture of muscles, fat, arteries and veins, as well as the branch of nerves that travels through the sacrum comes to mind. Likewise, he’s seen the shriveled result of a brain wracked with Alzheimer’s and touched the spongy texture of the lungs.

The three-dimensional learning that cadavers offer provide an advantage over those students strictly learning from plastic models or textbooks, he claims.

Carlson, a Nurses for Nursing Scholarship recipient and Army National Guard member, said when doing medical field training with fellow troops, he can clearly visualize the anatomical regions and layers of tissue when he’s working with patients because he’s dissected fat from the muscles in order to isolate nerves, veins and lymph nodes. His military buddies, on the other hand, who weren’t trained at Clark, often reference pages from a book.

“It’s not just a single layer of muscle in the leg; they would have to look further in the book to see the whole picture,” he said. This, he believes, gives him a critical learning advantage.

Carlson’s experiential education—learning by doing—in anatomy and physiology is thanks to a human cadaver laboratory. Clark’s is the largest in the state for community colleges, with five tables, and will be expanding to 11 tables. The college is currently building a 70,000 square-foot STEM facility that will include a second cadaver lab. The training that will occur in that building is expected to address the skills-gap shortage for health care and other science-based jobs in Washington.

There are 25,000 unfilled jobs in science, technology engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields in the state, with a projected increase to 50,000 by 2017. Eighty percent of such openings are in high-skill STEM and health care positions, according to a 2013 Washington Roundtable report.

A second cadaver laboratory within Clark’s STEM facility will help address many of these workforce education needs. The new space includes two technologically advanced classrooms each about 1,470 square feet and a 737-square-foot cadaver lab with six ventilation tables. Thanks to generous donors Steve and Jan Oliva, the lab will be known as the Steve and Jan Oliva Anatomy Lab.

Nursing student Dustin Carlson believes studying human cadavers accelerates his learning. Photo by Jenny Shadley

Second cadaver lab

There is no technology in the current cadaver lab—a 570 square-foot retrofitted storage room in a science building built in the 1950s. There are five stainless steel tables with pencil-wide ventilation holes framing the tabletop and bright, hot 200-watt lamps overhead. Exhaust ducts are attached at the foot table upon which the human cadavers are placed. The vapors from the preserved bodies are pulled down into the table and outside through the ducts. Despite its refurbished set up, the room exceeds health and safety codes for airborne chemicals, according to Rebecca Benson, Clark’s environmental health and safety supervisor.

The room is cramped and contains a narrow countertop with a deep sink and limited storage for teaching tools. During one academic quarter, more than 400 students pass through the lab participating in the practicum experiences. Given the limited space, there are constant teaching challenges.

A new cadaver lab will serve an additional 1,000 to 1,200 students annually, essentially doubling the college’s capacity and assuring that Clark fulfills its core themes of advancing accessibility and creating rich technological learning environments.

Non-heat lamps, two large-screen televisions and a camera allowing for the broadcast of images during teaching demonstrations only will be set up in the new space. The lighting will increase visibility for participants and reduce the desiccation that occurs when heat lights relentlessly beam onto chemically preserved cadavers.

Clark launches its first-ever bachelor’s degree in Dental Hygiene this fall and graduates are expected to earn their credential by 2016. This popular program, as well as Nursing, has a high demand for Anatomy and Physiology (A&P) courses, as they are required for the degree. But a constant waiting list makes scheduling the courses tricky.

“A good predictor of how students do in Nursing school is how they do in A&P,” said Mark Bolke, one of Clark’s three full-time, tenured biology instructors.

A second cadaver lab will allow the college to expand access to A&P courses to future students in Dental Hygiene, Nursing, Medical Radiography, Pharmacy and Phlebotomy. Students regularly share their appreciation for the chance to be hands-on when studying muscles, nerves, internal organs and blood vessels in situ.

“If I have to place a feeding tube into a patient’s stomach, I remember how big or small the esophagus can be…If I had to study from a book of drawings, my knowledge base would have been so much less,” said alumna Shannon Kysar, RN.

No more cats

Clark’s Anatomy and Physiology curriculum, like many other institutions nationwide, once relied on cats in its Biology program. For years, the college purchased specially treated animals that were injected with colored dye to help students identify veins, arteries and the hepatic portal system – a processing station in the abdominal cavity.

Former division chair and biology professor John Martin learned in 1988 that Lower Columbia College in Longview had one human cadaver for teaching purposes, and after doing research, discovered that University of Washington was making cadavers available for community colleges in the state, something normally reserved for medical universities.

In 1989, Martin took his case to Clark’s administration touting the learning advantages for the college’s health care students and cost savings – the specially treated cats were quickly becoming too expensive. Ultimately, he garnered their support, had an old storage room with an existing vacuum system converted into a lab and assembled two new down-draft tables for the bodies.

By the summer of 1990, the first two human cadavers, a male and female, were in place, a third table and a second female cadaver followed by 1995. The third one was constructed and eventually donated by the husband of an alumna, who owned a sheet metal manufacturing business, according to Martin.

By the late 1990s, a fourth table was built by former Clark welding instructor Pat Gonzales, and a fifth was added by early 2000.

Clark’s cadaver lab features lightening that is used in surgical rooms.

Willed Body Program

Today, Clark serves 1,030 students annually through its highly popular Human Anatomy and Physiology courses that utilize the five cadavers Clark receives annually from the Willed Body Program, through University of Washington’s School of Medicine’s Biological Structures Department. UW is the portal for all cadaver assignments for medical research and study in the state. Furthermore, Clark adheres to a strict state law that restricts photographic or video images of the cadavers and emphasizes a code of respect toward the human remains when working or speaking about the cadavers.

The A&P classes at Clark have become sought after; waiting lists grew over time and weekend classes, which had been available since the 1970s and used cats for dissection, filled. Students have been turned away from A&P classes for at least the last 10 years because they quickly reach capacity, according to Bolke, who teaches courses in human anatomy and physiology. The program also relies on adjunct instructors to teach lab.

Being able to provide students with hands-on learning is critical, according to Martin, who retired in 2007. He’s encouraged about the addition of a second lab; however, shortages in cadaver donations raises concerns about filling the six new tables.

Bolke isn’t overly concerned about the extra tables. If University of Washington can’t supply more cadavers initially, he’d consider putting some of the existing cadavers in the new space. The tissues will last longer, he believes, because the new surgical lights are less apt to dry out the bodies like in the existing lab’s overhead bulbs.

Another solution, said Martin, is Clark could negotiate to keep the cadavers for longer than the current one-year agreement or a cold room could be added to preserve the bodies.

Todd Olson, an anatomist at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York said that “anatomy is the foundation for the language of medicine: the language health care professionals use for communicating about patients.” Vast advances in health care require medical curriculums to keep pace and ultimately result in more prepared employees. Clark’s A&P courses, in unison with its cadaver laboratory, make this education affordable, accessible and meaningful for students.

Washington community colleges with cadaver labs

Clark College | Everett Community College

Green River Community College | Lower Columbia College

North Seattle College | Olympic College

Renton Technical College | Tacoma Community College

Published on 8/12/2015. Revised 8/23/19; 1/23/2020