The element of surprise

Professor Dietmeier demanded hard work and punctuality

Alumni revel in his teachings and the influence he had on their lives

By Rhonda Morin

Professor Roland Dietmeier was hard on his students. His former students remember him as demanding, quick-tempered, strict, intolerant of tardiness or absences and not generous with As.

In the next breath, those same alumni say he was the most influential instructor they had in their collegiate careers, or someone who cared about them personally and credit him for their success in life. They all agree that the rigors of his instruction paid off and left long-lasting impressions on them.

Gene Sargent ’52, remembers when a projector was playing loudly in a classroom next to the chemistry lab. Dietmeier abruptly stopped his lecture, walked next door and firmly told his colleague to “turn that projector down.”

He returned to his classroom, but the noise persisted. Dietmeier walked out again and proceeded to pull every single fuse in a nearby fuse box—shutting off electricity to the entire building. Colleagues poured out of their classrooms complaining that the lights suddenly went out or their equipment failed.

Sargent vividly recalls Dietmeier’s response: “When I say I want that projector volume down, I mean I want that projector turned down!”

This is one of many stories alumni have of their no-nonsense Chemistry professor during the 1950s and 1960s.

Makings of a teacher

Roland Dietmeier was raised in Minnesota with his six siblings. He studied Chemistry and played football at Carleton College, graduating with a bachelor’s in 1926. He taught high school and college for a time before entering graduate school and then marrying Gertrude Klaras in 1932. The couple had two children—Klaras and Roland—while he finished his master’s in Chemistry in 1936 from the University of Minnesota.

Roland Dietmeier over the years, seen with his granddaughter, top, and his wife Gertrude,

left. Photos provided by the family.

He worked next with the Forest Service replanting a national forest, and during that time the couple had a third child, Richard. As the United States entered World War II, Dietmeier moved his family to Montana where he taught physics to U.S. Army recruits at the University of Montana.

As the war drew to a close, Dietmeier explored finding a college teaching job and found a fit at Clark College, which on January 21, 1946, had re-opened having temporarily closed its doors during parts of the war period. Classes at that time were held in the basement of Vancouver High School and later at Ogden Meadows, a former housing development. By 1951, the college moved to its current main campus location in Vancouver’s Central Park on Fourth Plain Boulevard. Dietmeier set up his Chemistry labs and classrooms in these locations stocked with plenty of chalk for his infamous chalkboard writing assignments.

Cut out for chemistry

When Sargent enrolled in a Chemistry class in the early 1950s, he wasn’t sure if he was cut out for it. As a pre-dental student, he had to pass general Chemistry and Organic Chemistry, but he wasn’t yet confident in his skills.

Dietmeier’s advice was straightforward: “We’ll find out soon enough if you’ve got it or not.” The teacher ran down his litany of expectations: “You will never miss a class. If you’re not in the hospital, then you will be in class. You will never be late for class. All assignments will be passed in on time.”

Sargent took 20 credit hours that first quarter. “I was in class from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. and I studied until 11 p.m. I was in love at the time, but it would be a year and a half before I spent time with my future wife.”

The extra effort paid off. Between Dietmeier and Biology Professor Anna Pechanec, who was similarly strict, Sargent found his stride. He disciplined himself to study and worked hard for B’s and the A he earned in Organic Chemistry his second year.

“They taught me how to work. Roland Dietmeier, in particular, was the most influential person in my life,” said Sargent.

Sargent had a shot at getting into the University of Oregon dental school. Acceptance was based on a high grade-point average. Of the 700 applicants in 1952, a total of 77 were accepted and only one was from a community college—Sargent. He met the standard thanks to a last-minute change to his final Organic Chemistry letter grade. Dietmeier admitted he’d been hard on Sargent and switched his 94 grade from a letter B to a letter A.

After earning his doctor of medical dentistry (DMD) degree, he served as a captain in the Army for two years as a dentist, then opened a private practice in Burlington, Wash. He served patients for five decades.

“I’m indebted to Clark College,” said the 85-year-old.

Chemical reaction

Tom Wolford ’65 had aspirations to work in the science field. But he had a challenge. He is dyslexic, though he wasn’t diagnosed until well past his college days. Writing reactions on the chalkboard was very difficult. He’d write O2Si instead of SiO2 for a silicon and oxygen reaction.

“I can’t spell cat, but I know Ca stands for calcium because of Dietmeier,” he said.

Dietmeier told Wolford that he was a good enough student, but he simply didn’t put in enough effort.

Wolford rose to the task of memorizing the periodic table of elements and solubility table of ionic compounds. He went on to get a master’s in Chemistry at Western Washington University and a doctorate from the University of California at Davis and had a productive 22-year career with Crown Zellerbach Corp. He was also a college recruiter for University of Washington’s paper science program. Until his retirement three years ago, Wolford worked with Clark College’s Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) department to recruit students.

Flying erasers

Betty and Glenn Tribe were also Dietmeier’s students. Glenn attended Clark for one year in 1952 before transferring to Washington State University in Pullman. Betty attended for two years and completed her associate degree.

Dietmeier, they agree, was a taskmaster, and at 6 foot, 2 inches and broad-shouldered, an intimidating presence at the front of the class. He frequently encouraged students to compete against each other. Pop quizzes were standard and often the professor would acknowledge—by name—who answered questions correctly and who did not.

Memorizing elements and valences were a key part of the Chemistry class. Valences are the charges of ions formed from atoms. Ion charges then form the molecular structures of compounds.

Chalkboards framed the classroom on three sides and students were routinely called upon to write reactions or compounds on the chalkboard in front of the class. If you didn’t do your homework, the Tribes recall, the next day’s class was painful.

“I had no idea about valences. Chemistry class was a drilling experience for me,” said Glenn.

Betty, however, studied chemistry in high school, which gave her an advantage. “I knew all about valences and still do to this day. I sailed through General Chemistry,” said Betty, who after raising her family, returned to college for a Fine Arts degree.

For those, like Glenn, who stood facing the chalkboard, frantically trying to recall what the valence of chloride was in hydrogen chloride, the sound of an eraser passing their ears or a piece of chalk splitting as it smashed against the board was a common occurrence.

“I’d be told it might be to my advantage to study more that evening,” said Glenn, who went on to obtain an advanced degree, a Professional Engineer license and had a career as a mechanical engineer.

Women in STEM

Dietmeier was particularly interested in getting more women involved in STEM, according to his daughter Klaras Dietmeier Ihnken.

“He’d invite his female students to dinner on Sunday with our family,” said Ihnken. She recalls him telling the women that they must finish their degrees and find a job in STEM in addition to raising their families.

“This was a regular conversation at our supper table,” said Ihnken, “This was post-World War II and my father saw that women needed training and education to go to work.”

Ihnken was also a pupil of her father’s disciplined work ethic, which in fact prepared her for a career as a high school teacher and mother. She studied under Dietmeier at Clark during the day, then returned home with her father and to the rest of her family to study at night.

The learning process for Ihnken and the rest of Dietmeier’s students, was rich, challenging and rewarding. Clark has a tradition of such a process: former and current faculty are a special group of professionals who go to great lengths to help students understand and apply what they learn. And though classroom interactions have evolved since Dietmeier’s tenure, the premise still exists: Do your homework, think critically through a problem and never, ever be late for class.

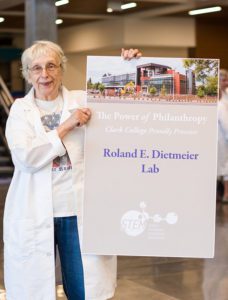

The Roland Dietmeier Chemistry Lab

Clark’s new STEM building opens officially during a ribbon cutting ceremony on October 3.

Anonymous donors contributed $265,000 in honor of Professor Roland Dietmeier. One of the spacious rooms on Chemistry’s second floor now carries the name: Roland Dietmeier Chemistry Lab.

Klaras Dietmeier Ihnken proudly displays the name of a new chemistry lab in honor of her father, Roland Dietmeier, who taught at Clark in the 1950s and 1960s.

White erase boards line the walls in place of the old green chalkboards, with dry erase markers substituted for the yellow and white chalk. The erasers haven’t changed a whole lot; they are a similar size to their ancestors, though perhaps a little lighter. Wonder if they sail through the air at the same speed as chalk erasers?

There are many opportunities still available to name spaces in the new STEM building. Take part in the power of philanthropy by contacting Joel B. Munson, Sr. VP of development at jmunson@clark.edu or 360.992.2428.